The Underground Railroad in NJ

A DESCRIPTION OF THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD ROUTES THROUGH NEW JERSEY

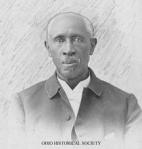

New Jersey was intimately associated with Philadelphia and the adjoining section in the underground system, and afforded at least three important outlets for runaways from the territory west of the Delaware River. Our knowledge of these outlets is derived solely from the testimony of the Rev. Thomas Clement Oliver, who, like his father, traveled the New Jersey routes many times as a guide and conductor.

Rev. Oliver

Rev. Oliver

Probably the most important of these routes was that leading from Philadelphia to Jersey City and New York. From Philadelphia the runaways were taken across the Delaware River to Camden, where Mr. Oliver lived, thence they were conveyed northeast following the course of the river to Burlington, and thence in the same direction to Bordentown. In Burlington, sometimes called Station A, a short stop was made for the purpose of changing horses after the rapid driver of twenty miles from Philadelphia. The Bordentown station was denominated Station B east. Here the road took a more northerly direction to Princeton, where horses were again changed and the journey continued to New Brunswick. 2

Just east of New Brunswick the conductors sometimes met with opposition in attempting to cross the Raritan River on their way to Jersey City. To avoid such interruption the conductors arranged with Cornelius Cornell, who lived on the outskirts of New Brunswick, and, presumably, near the river, to notify them when there were slave-catchers or spies at the regular crossing. On receiving such information they took a by-road leading to Perth Amboy, whence their protégés could be safely forwarded to New York City.

When the way was clear at the Raritan, the company pursued its course to Rahway; here another relay of horses was obtained and the journey continued to Jersey City, where, under the care of John Everett, a Quaker, or his servants, they were taken to the Forty-Second Street railroad station, now known as the Grand Central, provided with tickets, and placed on a through train for Syracuse, New York.

The second route had its origin on the Delaware River, forty miles below Philadelphia, at or near Salem. This line, like the others to be mentioned later, seems to have been tributary to the Philadelphia route traced above. Nevertheless, it had an independent course for sixty miles before it connected with the more northern route at Bordentown. This distance of sixty miles was ordinarily traveled in three stages, the first ending at Woodbury, twenty-five miles north of Salem, 3 although the trip by wagon is said to have added ten miles to the estimated distance between the two places; the second stage ended at Evesham Mount; and third, at Bordentown.

The third route was called, from its initial station, the Greenwich line. This station is vividly described as having been made up of a circle of Quaker residences enclosing a swampy place that swarmed with blacks. One may surmise that it made a model station. Slaves were transported at night across the Delaware River from the vicinity of Dover, in boats marked by a yellow light hung below a blue one, and were met some distance out from the Jersey shore by boats showing the same lights. Landed at Greenwich, the fugitives were conducted north twenty-five miles to Swedesboro, and thence about the same distance to Evesham Mount. From this point they were taken to Mount Holly, and so into the northern or Philadelphia route.

Still another branch of this Philadelphia line is known. It constitutes the fourth road, and is described by Mr. Robert Purvis as an extension of a route through Bucks County, Pennsylvania, that entered Trenton, New Jersey, from Newtown, and ran directly to New Brunswick and so on to New York.

From Wilbur H. Siebert, The Underground Railroad (1898) on NJ History for Kids

About the Underground Railroad

ABOUT THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

The Underground Railroad was a network of secret routes and safe houses used by 19th-century slaves of African descent in the United States to escape to free states and Canada with the aid of abolitionists and allies who were sympathetic to their cause. The term is also applied to the abolitionists, both black and white, free and enslaved, who aided the fugitives. Various other routes led to Mexico or overseas. An "Underground Railroad" running south toward Florida, then a Spanish possession, existed from the late 17th century until shortly after the American Revolution. However, the network now generally known as the Underground Railroad was formed in the early 19th century, and reached its height between 1850 and 1860. One estimate suggests that by 1850, 100,000 slaves had escaped via the "Railroad".

The escape network was not literally underground nor a railroad. It was figuratively "underground" in the sense of being an underground resistance. It was known as a "railroad" by way of the use of rail terminology in the code. The Underground Railroad consisted of meeting points, secret routes, transportation, and safe houses, and personal assistance provided by abolitionist sympathizers. Participants generally organized in small, independent groups; this helped to maintain secrecy because individuals knew some connecting "stations" along the route but knew few details of their immediate area. Escaped slaves would move north along the route from one way station to the next. "Conductors" on the railroad came from various backgrounds and included free-born blacks, white abolitionists, former slaves (either escaped or manumitted), and Native Americans. Church clergy and congregations often played a role, especially the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), Congregationalists, Wesleyans, and Reformed Presbyterians as well as certain sects of mainstream denominations such as branches of the Methodist church and American Baptists. Without the presence and support of free black residents, there would have been almost no chance for fugitive slaves to pass into freedom unmolested.

To reduce the risk of infiltration, many people associated with the Underground Railroad knew only their part of the operation and not of the whole scheme. "Conductors" led or transported the fugitives from station to station. A conductor sometimes pretended to be a slave in order to enter a plantation. Once a part of a plantation, the conductor would direct the runaways to the North. Slaves traveled at night, about 10–20 miles (15–30 km) to each station. They would stop at the so-called "stations" or "depots" during the day and rest. The stations were often located in barns, under church floors, or in hiding places in caves and hollowed-out riverbanks. While the fugitives rested at one station, a message was sent to the next station to let the station master know the runaways were on their way.

The resting spots where the runaways could sleep and eat were given the code names "stations" and "depots," which were held by "station masters". "Stockholders" gave money or supplies for assistance. Using biblical references, fugitives referred to Canada as the "Promised Land" and the Ohio River as the "River Jordan", which marked the boundary between slave states and free states